This is a question I am glad to see in the media. First off this is a long article and I will post a few quotes and a pictorial. What do we really know about the life cycle of the electric vehicle? Not much, they are too new to have that kind of data if there was any way to keep track of it which there isn't. No present of future programs, testing sites, data collection plans at all. How about the manufacturing - the battery the vain of all things EV is a big culprit. It uses natural resource to be mined in ways we have no control over. We still have the issue it is more cost efficient to mine new lithium than to recycle it . We know EV's produce 0 emissions but really with out a tail pipe how do we know that for sure. The biggest for last if you are in an area that uses coal for electric power any good of owning an ev is now null and void. At this point we know for sure the big push for EV's is the government wanting a 30% decrease in emission before 2030.

https://www.ft.com/content/a22ff86e-ba37-11e7-9bfb-4a9c83ffa852

https://www.ft.com/content/a22ff86e-ba37-11e7-9bfb-4a9c83ffa852

Please use the sharing tools found via the email icon at the top of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach of FT.com T&Cs and Copyright Policy. Email [email protected] to buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found at https://www.ft.com/tour.

https://www.ft.com/content/a22ff86e-ba37-11e7-9bfb-4a9c83ffa852

YESTERDAY Patrick McGee in Frankfurt 352 comments

The humble Mitsubishi Mirage has none of the hallmarks of a futuristic, environmentally friendly car. It is fuelled by petrol, runs on an internal combustion engine and spews exhaust emissions through a tailpipe.

But when the Mirage is assessed for carbon emissions throughout its entire lifecycle — from procuring the components and fuel, to recycling its parts — it can actually be a greener car than a model by Tesla, the US electric vehicle pioneer.

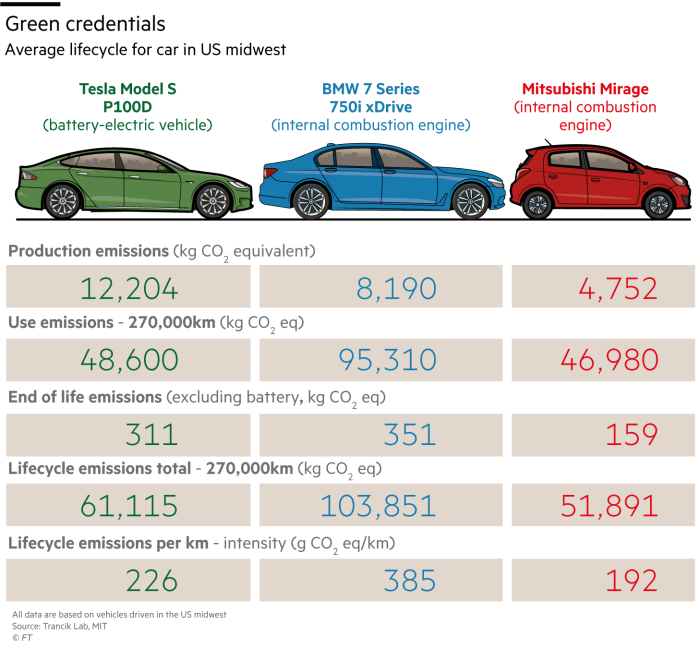

According to data from the Trancik Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a Tesla Model S P100D saloon driven in the US midwest produces 226 grammes of carbon dioxide (or equivalent) per kilometre over its lifecycle — a significant reduction to the 385g for a luxury 7-series BMW. But the Mirage emits even less, at just 192g.

Share this graphic

The MIT data substantiate a study from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology last year: “Larger electric vehicles can have higher lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions than smaller conventional vehicles.”

The point of such comparisons is not to make the argument for one technology over another, or to undermine the case for “zero-emission” cars. But they do raise a central issue about the industry: are governments and carmakers asking the right questions about the next generation of vehicles?

Policymakers are pushing the car industry toward a new era, but neither Europe, America nor China have actually set up the appropriate regulatory apparatus to differentiate among electric vehicles and judge their environmental merits. The idea that some combustion engine cars can be greener than some “zero-emission” electric vehicles simply does not make sense in the current regulatory environment.

From a government standpoint, all electric vehicles are equally green — regardless of whether they are big or small, produced efficiently or with great waste, or powered by electricity generated by solar energy or coal.

“Electric vehicles are zero-emission by definition,” says Roland Doll, innovation officer at InnoEnergy, a group supporting sustainable energy. “[Regulators] only measure what comes out of the exhaust pipe. Well, there is no exhaust pipe.”

Testing of a lithium-ion battery at a BMW factory © Bloomberg

To capture electric cars’ full environmental impact, regulators need to embrace lifecycle analysis that takes into account car production, including the sourcing of rare earth metals that are part of the battery, plus the electricity that powers it and the recycling of its components. Such studies have become popular among researchers who favour direct comparisons with petrol and diesel cars. If these studies were to inform regulatory policy, analysts say it would have a big impact on what cars will be on the road in the coming decades.

As things stand, a small car like the Mirage could be illegal to drive in cities across Europe, the UK and China by 2030, as incoming bans on combustion engine cars will pay no attention to fuel economy or efficiency of production.

“Politicians are setting policy in a vacuum,” says Harald Hendrikse, auto analyst at Morgan Stanley.

10kg

Cobalt needed for a 100kW electric vehicle — a typical smartphone has less than 10 grammes of the metal in its battery, according to Liberum

On Wednesday Brussels proposed new rules to promote electric vehicles, threatening financial penalties for carmakers that fail to reduce tailpipe emissions by 30 per cent between 2020 and 2030. But at present there are no plans for lifecycle analyses of the merits of electric vehicles, nor are they expected soon.

Instead, the industry is being incentivised to introduce electric vehicles, generating a backlash from executives who worry there is not yet adequate knowledge of the implications.

“We are moving from a technology-neutral era into an instruction to go electric,” Carlos Tavares, chief executive of French carmaker PSA, said at the Frankfurt Motor Show in September. “So if, in 20 or 30 years, there are health or safety issues, they will be in the hands of governments. If there’s any problem, the responsibility is in their hands.”

Workers at a Mitsubishi Motors assembly line in the Philippines © Bloomberg

Lifecycle studies show that the idea of “zero emissions” is misleading, at least for now. Too much energy is consumed in the manufacturing process of lithium-ion batteries, and to recharge them, for the environmental impact to be nil.

Please use the sharing tools found via the email icon at the top of articles. Copying articles to share with others is a breach of FT.com T&Cs and Copyright Policy. Email [email protected] to buy additional rights. Subscribers may share up to 10 or 20 articles per month using the gift article service. More information can be found at https://www.ft.com/tour.

https://www.ft.com/content/a22ff86e-ba37-11e7-9bfb-4a9c83ffa852

YESTERDAY Patrick McGee in Frankfurt 352 comments

The humble Mitsubishi Mirage has none of the hallmarks of a futuristic, environmentally friendly car. It is fuelled by petrol, runs on an internal combustion engine and spews exhaust emissions through a tailpipe.

But when the Mirage is assessed for carbon emissions throughout its entire lifecycle — from procuring the components and fuel, to recycling its parts — it can actually be a greener car than a model by Tesla, the US electric vehicle pioneer.

According to data from the Trancik Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a Tesla Model S P100D saloon driven in the US midwest produces 226 grammes of carbon dioxide (or equivalent) per kilometre over its lifecycle — a significant reduction to the 385g for a luxury 7-series BMW. But the Mirage emits even less, at just 192g.

Share this graphic

Share on Twitter (opens new window)

Share on Facebook (opens new window)

The MIT data substantiate a study from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology last year: “Larger electric vehicles can have higher lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions than smaller conventional vehicles.”

The point of such comparisons is not to make the argument for one technology over another, or to undermine the case for “zero-emission” cars. But they do raise a central issue about the industry: are governments and carmakers asking the right questions about the next generation of vehicles?

Policymakers are pushing the car industry toward a new era, but neither Europe, America nor China have actually set up the appropriate regulatory apparatus to differentiate among electric vehicles and judge their environmental merits. The idea that some combustion engine cars can be greener than some “zero-emission” electric vehicles simply does not make sense in the current regulatory environment.

From a government standpoint, all electric vehicles are equally green — regardless of whether they are big or small, produced efficiently or with great waste, or powered by electricity generated by solar energy or coal.

“Electric vehicles are zero-emission by definition,” says Roland Doll, innovation officer at InnoEnergy, a group supporting sustainable energy. “[Regulators] only measure what comes out of the exhaust pipe. Well, there is no exhaust pipe.”